Building Product With Ground Rules

I Hate Rules, So Why Set Product Ground Rules?

To consistently make the right decisions during a project, I’ve found setting some core “product ground rules” help ensure the team doesn’t go off-track. Even when working as an individual on personal projects, I find it invaluable to have some core principles to keep from going down rabbit holes. It’s the best way not to flip-flop on already made decisions and help keep scope prioritized and focused on the MVP.

The mission for this site was to keep things simple; while delivering a robust, lightning fast site that’s focused on presenting readable content.

Below are the rules I set (and mostly stuck to) while making the decisions for this project. They serve as a simplified, but a real-world example of the ground rules concept. They weren’t hard and fast, but they helped to stay on track and deliver the project quickly.

Rule 1: No Software Dependencies

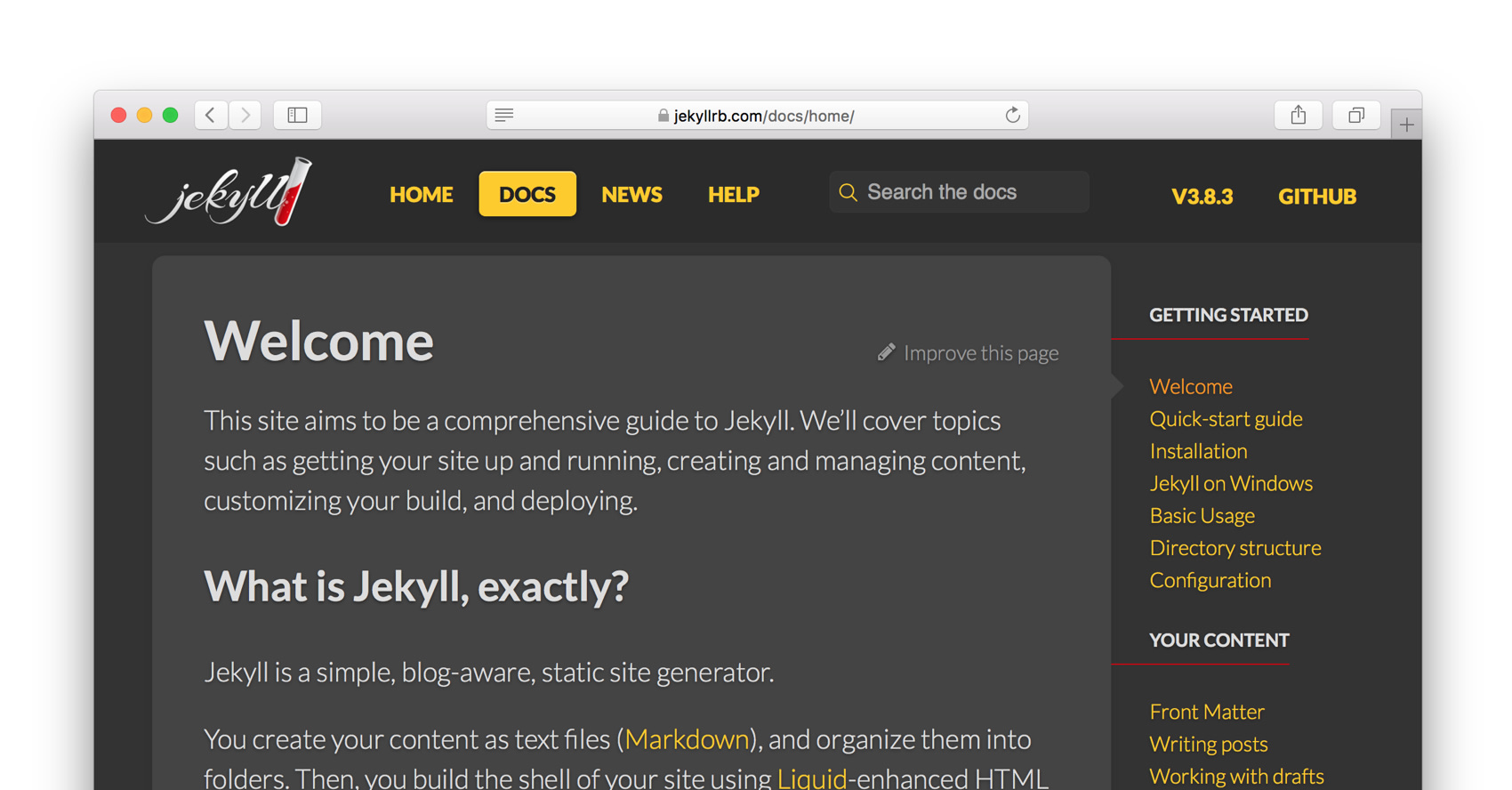

This one was by far the hardest to consistently follow. The first “no software” decision to be made was the platform for the backend. The obvious choice would have been to use Wordpress. Nothing against Wordpress, I’ve used it in the past on many projects, and it was precisely the right tool for the job, just not for this site. I didn’t need a database or any dynamic content. If I did, I would have considered Wordpress. Therefore, keeping with the rest of my ground rules all CMS systems were out. I had a suspicion that a static site generator would be the best option for this project and that’s exactly where I landed.

Static site generators have come a long way, and there are more of them today than ever before. Jekyll, Hexo, Hugo, Octopress, Pelican, Brunch etc… Here’s a list from 2016 of the “Top Ten” if you’re interested. Again, this is where ground rules help make decisions I can live with. All of these are great, and all of them would probably have done the job well. Then rules #2 and #3 came into play: I didn’t want to use the command-line or maintain a server. More on those in a minute, ultimately this led me to Jekyll. Jekyll was also a good choice because I’ve used it in the past and liked it, so I felt it would be less cumbersome to set up and easier get rolling.

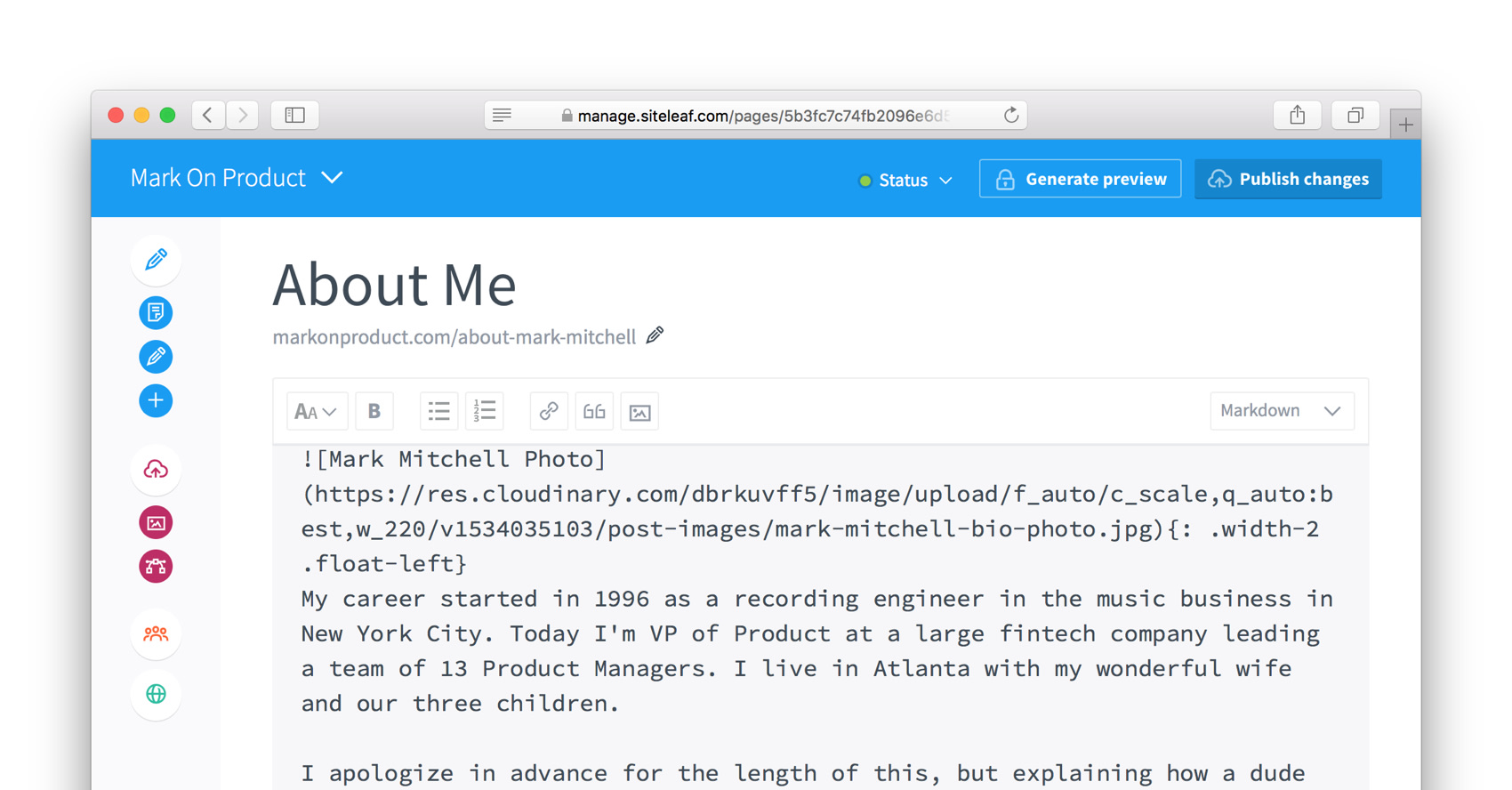

There was one more thing that factored into the platform decision, while I didn’t want a CMS, I also didn’t want to be in “developer mode” all the time. In other words, sometimes I want to be in coding mode and other times I want to be in writing mode. When I’m in writing mode, I prefer not to be in a code editor. There’s no real reason why it’s just how my brain works. Therefore, if I could have some form of a CMS front end that would be helpful, not a hard requirement - more of a “nice-to-have.”

To meet this need, I went with Siteleaf. It’s a nice “front end” to static Jekyll sites that makes doing quick updates easy. I could use it within my ground rules because it’s not a dependency. I can stop using it tomorrow, open my site files in a code editor and off we go. It’s a win!

Rule 2: No Command-line

Wait - a static site generator with no command-line; dude are you nuts? Nope (well yeah a little). It’s why I set the ground rules. See here’s the thing, I’ve never been a command-line “commando.” I can certainly use it, but I’ve never been good at it. In the past when using it for GIT, a task runner, or installing NPM modules - something ALWAYS goes wrong. Not “end of the world wrong” but wrong enough that I have to spend 15 minutes understanding an error message and then tweaking a config file.

I get it - it’s one of the most powerful tools on my machine, I don’t disagree - it just wasn’t for me on this one. Plus as I started to think about where I wanted to host this site, there was one right answer that allowed me to get around this ground rule.

Because this is a personal project and I’m making all the decisions, I could choose what rules I could break, and I did break a few.

It would be silly to build a responsive website and not use a CSS compiler. Surely it can be done, and I considered it, but SASS is my go-to, and after trying to avoid it for a little while - when it came to media-queries not using a mixin for those made little sense. So I added a software dependency. The way I justified it was “if I am adding a dependency, make it one that could be easily replaced with something else later if needed.” So I added CodeKit into the fold. It’s a Mac-based tool that does many things. For me, it’s just combining, processing and minifying my .scss files into an include file that Jekyll then inserts into the head. More on that later.

Rule 3: Open Source The Code

I’ve used open source code thousands of times for so many things; I’m sure most of us have at this point. Aside from the obvious benefit of open source code is free, I’ve always valued the community built and battle-tested aspect of it. As I look back and think about the most important thing I’ve gotten from using open source code, it’s the ability to learn from it. Having access to all of a project’s files to edit, contribute, and read comments on GitHub, etc. is a fantastic way to learn.

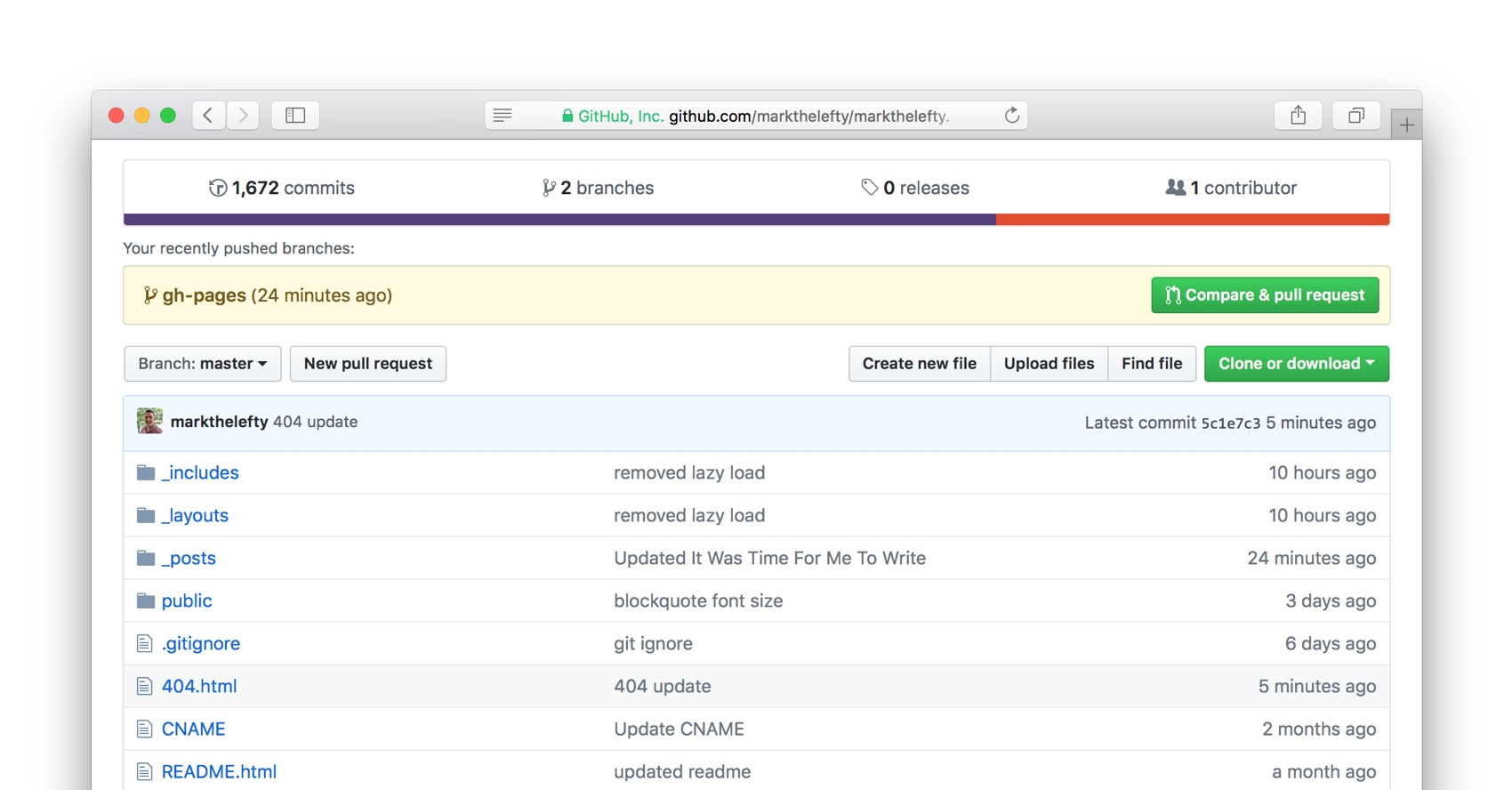

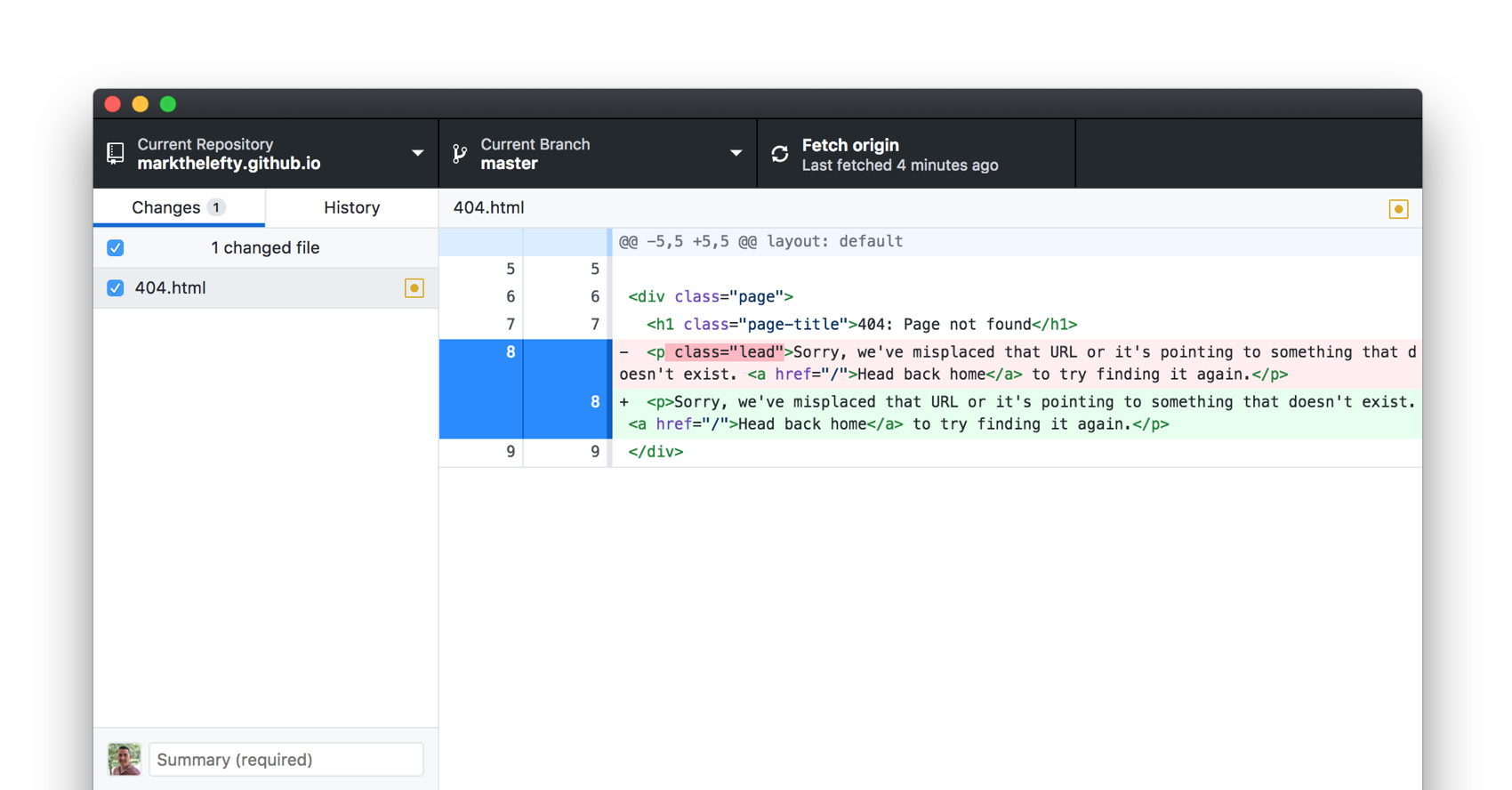

Seeing how others approach the same coding problems is probably the best way to learn. I decided on this project I would live out in the open. There’s nothing special about what’s behind this site, but as part of my “giving back” mantra - it’s all yours. It’s an open repo on GitHub - have at it. Like I said it’s nothing special, but I did solve a few coding challenges. If there’s something useful for you - feel free to use it.

Rule 4: No Server To Maintain

There are things I’m good at, and then there’s server administration. It’s just one of those things I’ve never really worked hard enough at to master. In the past when using shared hosting or a VPS setup there were times when it felt like I spent days doing server maintenance. I always felt like “dude I’m paying you for this thing, why can’t you do that”? In truth it’s a balance, having access to the root directory of a server can solve many problems - and cause some good ones too!

This project had cloud hosting written all over it. I knew the config would be simple, and I didn’t have to consider a bunch of “but what if we want X in the future” questions. I thought about AWS, Google Cloud and Azure. I’ve used AWS quite a lot, but haven’t used Azure or Google Cloud really at all. Was this the time to take the plunge with one of them to learn and play? Probably, but ultimately I chose not to because it felt too much like I was breaking rule #1 (No Dependencies). Sure I could move from one cloud provider to another if I wanted to, but setting it all up would be a hassle. I didn’t need it.

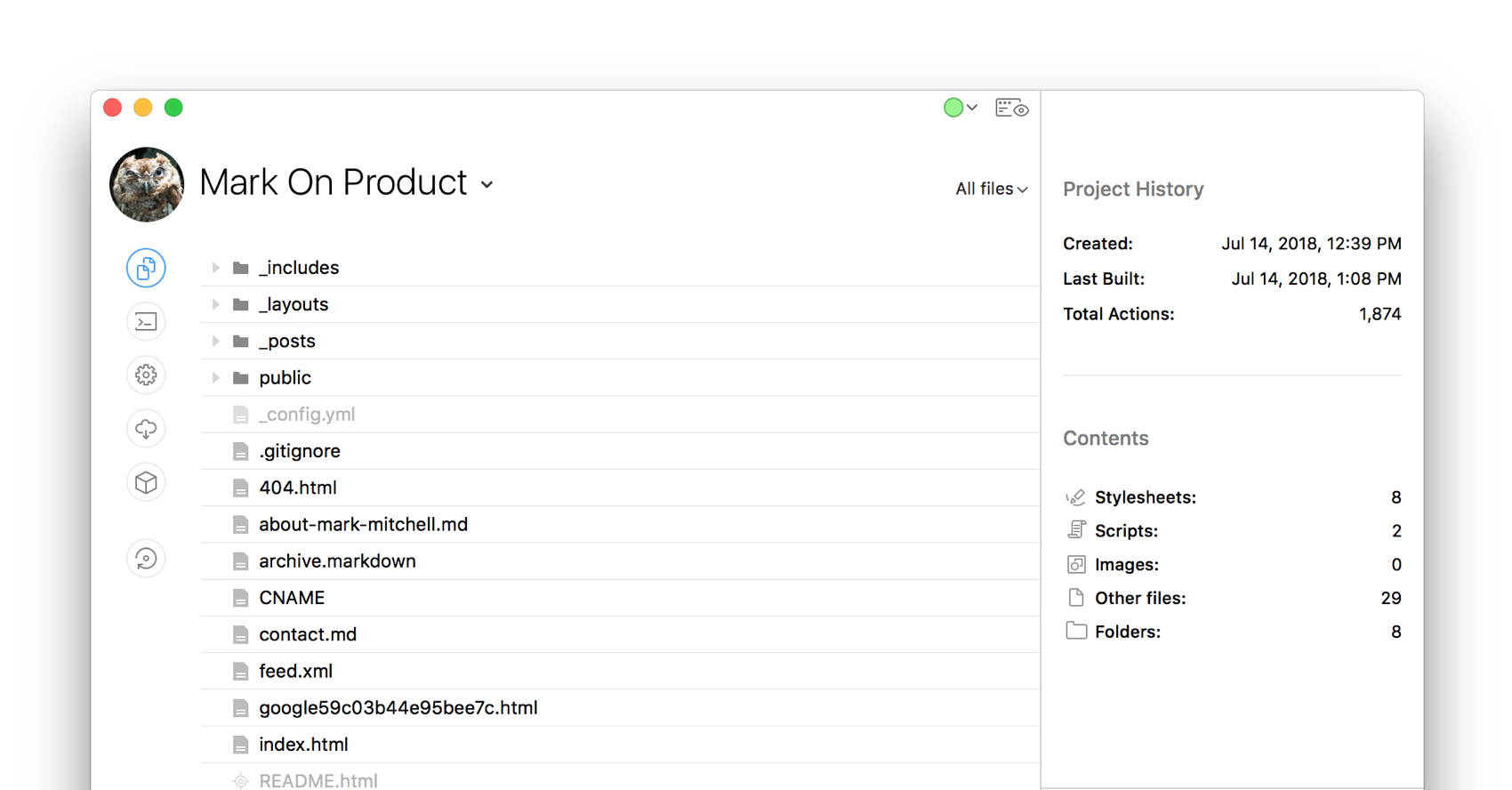

By now you can probably see where I’m going, I ended up using GitHub pages. I figured I’d give it a shot because it has support for Jekyll built-in. In other words, make a change to the markdown files on your local machine, commit the change to the master branch and voila - GitHub runs the build, and your site is updated.

GitHub pages did introduce a software dependency though - if you’re counting it’s the second. “How am I going to manage the GitHub repo with no common-line tool”? I decided to use the GitHub Mac app, I’m familiar with it, and like CodeKit, if I had to switch it out, there are many options like Tower for example. Alternatively, if I had to - I could use the command-line.

If you’ve ever considered using GitHub pages for a project - I highly recommend it. It’s fast, easy and free (for one site), I’ve been impressed. So there it was - I was “serverless.” Sidenote: Does the term “serverless” feel like the wrong word for the setup? That’s to say it’s not wrong, but it’s not right either? A future post on that I suppose.

Rule 5: No Huge Front End Framework

Using a front end CSS/JS framework can be incredibly powerful, and I recommend them. Bootstrap, Semantic UI, Foundation, Materialize etc. are all very good for their intended purpose. Here’s a list of the “Top Ten” in 2018 if you’re interested. I’ve used Bootstrap many times, and it’s great. It’s especially useful if you’re working with a large development team on a large application. It helps forge a unified approach to how the UI is designed and coded across teams and the organization.

For my site, I decided they’d be overkill for the following reasons:

- Rule #6 – site speed, I wanted this site to be fast, so I didn’t want to include a single line of CSS that I wasn’t using.

- As a content-forward blog, I didn’t need 85% of the components.

- I wanted to use little or NO JavaScript. Nothing against it, I just tried to minimize it as a dependency, and I didn’t want to use a JS library.

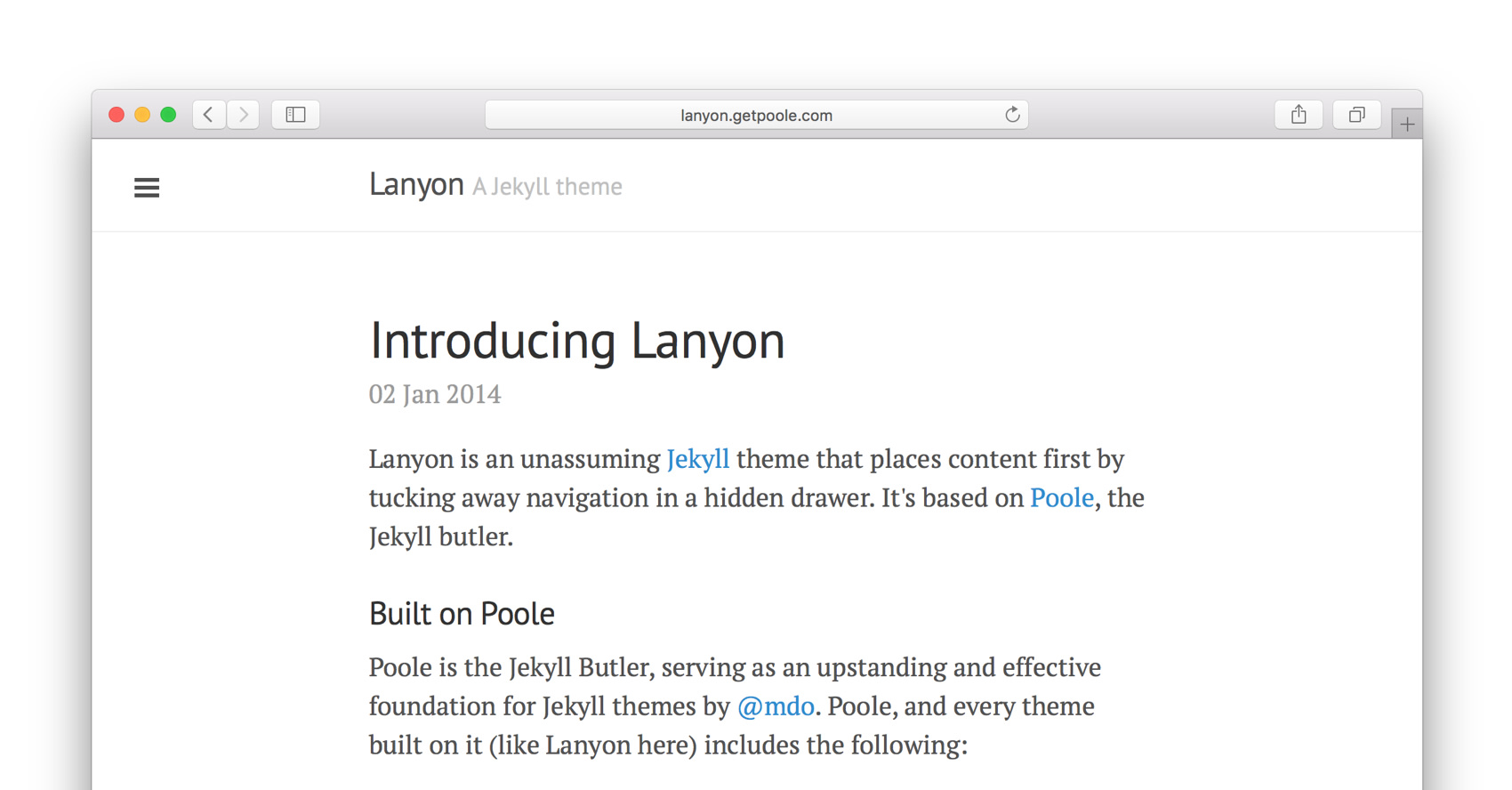

In the end, this was a fairly easy rule to follow. I spent more time than I would have liked coding HTML and CSS, but I used the Lanyon theme as a starter, giving me a good base to work from.

Rule 6: It Must Be Fast As A Giselle

This rule was probably the most challenging to adhere to throughout the build consistently. More than anything else, I wanted the site to deliver a great user experience - most importantly page speed. While working to make it fast, initially it felt like I was making many tradeoffs. In the end, most of these choices turned out to be short-term challenges as opposed to real long-term trade-offs. I found I had to be very disciplined with each line of code that was added to a page.

In the end, many small tweaks added up to a very fast site. The single thing that made the most significant impact was injecting the CSS directly into the head of each page. At first, I wouldn’t say I liked the idea, but I couldn’t believe the impact it had on performance. It also wasn’t an issue for my workflow because I have CodeKit minify and auto-prefix the .scss file and produce it as a Jekyll include that gets added to every page on the build.

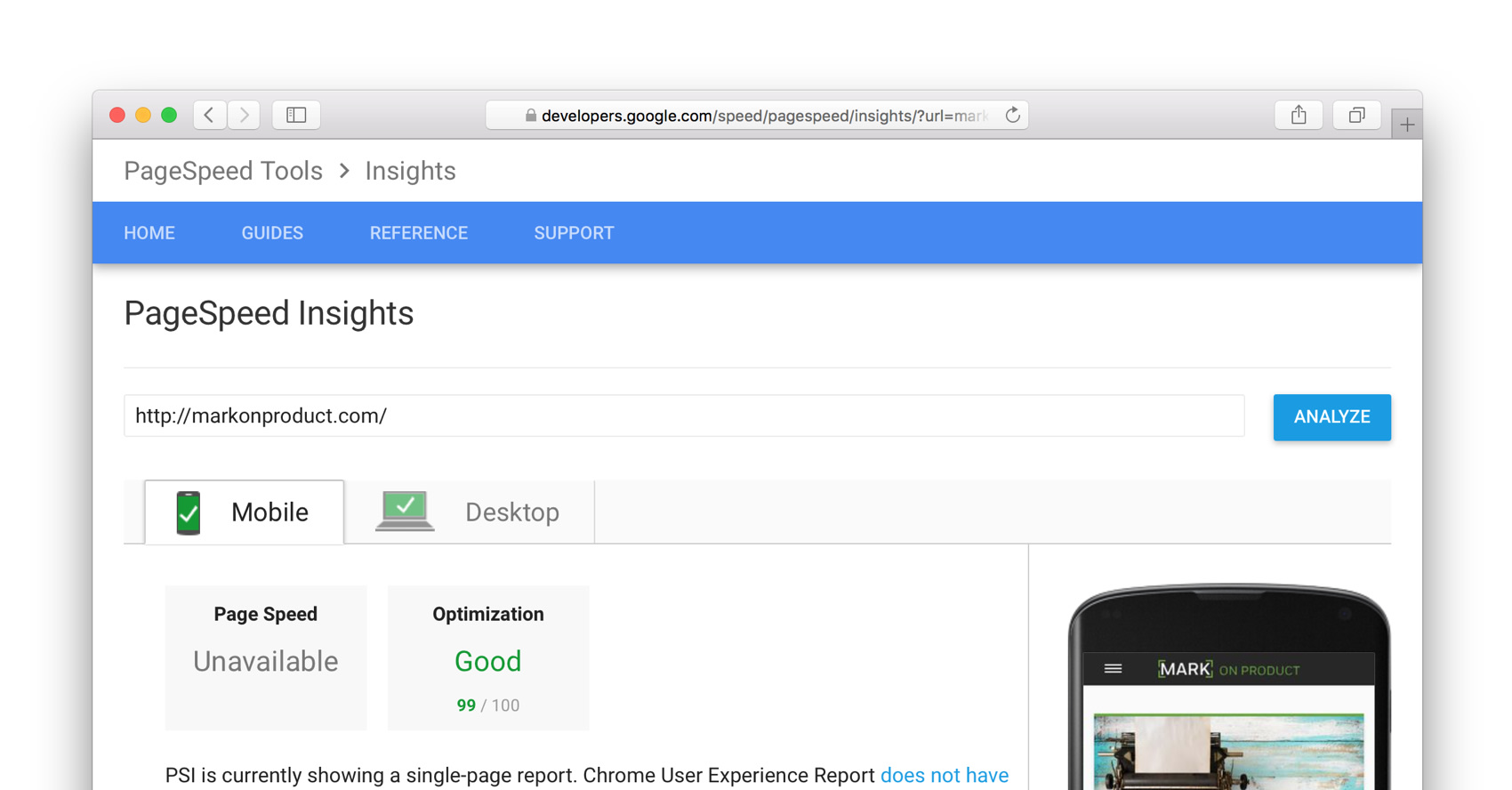

I also added CloudFlare as a CDN – no question it helped speed things up all around as well. The rest of the optimizations are fairly standard. They all add up to a 98-99 score from the Google PageSpeed tool. It’s not the score itself that mattered; instead, during the build the tool helped me evaluate if something I was trying to add to a page was worth the cost. Again a ground rule.

Rule 7: Do Not Pay $7 x 4

This final one is more a principle of convenience over anything else. While I LOVE supporting startups, independent software developers, and small businesses alike – I feel like everything in the universe is slowly coming with a small monthly fee. It’s not the actual cost I have an issue with; it’s maintaining an active credit card with 30 websites that seems to be the struggle. I think there’s a good start-up idea in there somewhere, but that’s for another time.

This basic rule was not to use a bunch of services that all come with small monthly charges. Better yet, I challenged myself to see if I could pull this whole thing off with NO monthly fees. I figured if someone else who had zero dollars to spend wanted to do this could they get this thing off the ground with no recurring monthly costs? Yep, 100%.

You will need to buy a domain name and maintain that every year. That will cost about $12-$15/year depending on where you go. However, besides that I’m incurring no other monthly costs. Here’s a breakdown of all the services used:

| Provider | Item | Cost Details |

|---|---|---|

| GitHub Pages | Hosting | Free - One site per user for public repo |

| Siteleaf | CMS System | Free - Developer plan meets my current needs |

| Typekit | Web Fonts | Free - Two free fonts, 25k page views/ month |

| Wufoo | Contact Form | Free - Up to 5 forms on the free plan |

| Cloudflare | CDN | Free plan meets my needs |

| Cloudinary | Image Hosting | Free - up to 10GB |

Conclusion

In the end, these ground rules forced me to stay on track focus on the MVP scope. It also allowed me to make decisions and stick with them, instead of remaking the same decisions with different outcomes. The site is fast, open source, and free to operate. Most importantly it delivers a content first approach designed for easy reading.